|

| Photo credit: malik ml williams on Flickr |

Answer: They're all non-main characters that many readers fell in love with. They also all happen to be male with relatively awesome names, but that's not the point.

Point is, these five guys developed a pretty extensive fan base, despite the fact that most of them were side characters. So how does that happen? How do authors write characters that fans falls so in love with that when some of them meet untimely ends, readers shed actual tears over the loss?

Let's take a quick look at each of the characters:

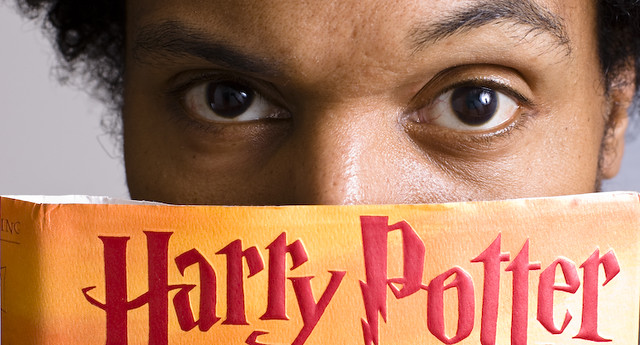

- Sirius Black (Harry Potter by J.K. Rowling). Sirius Black is one of my personal all-time favorite characters ever. He's a highly misunderstood man who spent years of his life trapped in the worst kind of prison imaginable for a crime he didn't commit, Harry's only hope at a "normal" life in a loving home, fiercely protective of his godson (but not to the point that he tries to shelter him), and armed with enough wit to make Snape blush. Combined with the fact that he's an adorable/badass dog half the time, there isn't much not to like about Sirius.

- Finnick Odair (Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins). Finnick is attractive, witty, infuriates/embarrasses Katniss on more than one occasion, and turns out to have to have a horrible past that makes you feel guilty for misjudging him as a total tool in Catching Fire (or maybe that was just me). Top that off with his unconditional love for a fellow ex-tribute who isn't all there, Finnick earns his spot as a fan favorite pretty quickly.

- Robin "Puck" Goodfellow (Iron Fey Series by Julie Kagawa). (Slight spoiler) Puck is Meghan's long-time best friend and secret guardian with a sharp tongue and penchant for tricks and trouble-making, so when he gets friend-boxed, you can't help but feel bad for the poor guy. Furthermore, when he remains loyal to Meghan despite his unrequited love, readers love him all the more.

- Kenji Kishimoto (Shatter Me by Tahereh Mafi). I'm not spoiling much when I say we all know Juliette isn't going to fall for Kenji—that much is pretty clear right from the beginning. But we can't help but admire his spirit when he tries to woo her over to him anyway (and make us laugh while attempting to do so), and plus there's the whole risking-his-life-to-help-Juliette-thing.

- Remus Lupin (Harry Potter by J.K. Rowling). After Sirius, Remus was probably my second-favorite minor Harry Potter character (tied with the Weasley twins), and I felt it important to include him because unlike the previous four, Remus is not funny. He's a very intense and serious character, largely afraid of himself and what he might do during a certain phase of the moon, and is entirely loyal to his friends and loved ones. Readers feel bad for Remus, and when he finds happiness we can't help but be glad that something good has finally come his way.

They're all characters readers became emotionally invested in. They made us laugh and cry and sympathize with them. We learned about their darkest secrets and what makes them happy, what scares them and what makes them angry. Their creators didn't write them lightly—they're carefully written and fully-developed characters that we as readers can't help but love.

The lesson is this: in order to write characters that your readers love, you need to invest just as much time and effort to get to know them as you did your protagonist. If you want your readers to remember the names of more than just your MC, you need to take time to really understand what makes your side characters tick, so that when time comes to write them, they feel just as real as your major characters.

As a writer, you have to fall in love with your side characters first. Once you do, writing them so that your readers adore them just as much as you do will come that much easier.

Who are your favorite side characters? What made you love them as much as you do?