|

| Photo credit: 401 (K) 2012 on Flickr |

How to Be an Incredible, Awe-Inspiring Writer Swimming in Bundles of Cash*

- Dream up the Golden Book Idea. The easiest way to come up with the idea that's going to make you richer than the Queen of England is to take previously successful books and mash them together. Twilight meets The Hunger Games meets Harry Potter meets Eat, Pray, Love. Star Wars meets Eragon meets Anne of Green Gables meets The Vampire Diaries meets The Notebook. The Lord of the Rings meets The Little Prince meets The Da Vinci Code meets The Very Hungry Caterpillar meets The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. You get the idea.

- Tell everyone about your brilliant novel. You'll also want to start calling literary agents at this stage. It's only fair that you give them the heads up that something that's about to change the literary world forever is in the works.

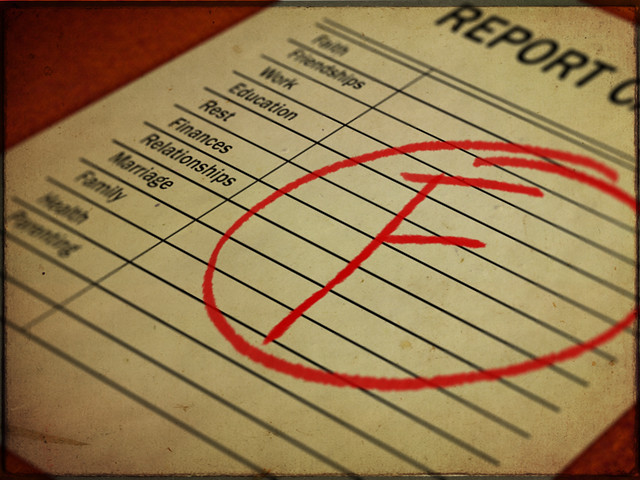

- Don't read. Reading is a waste of time and will only pollute your incredible writing skills. Don't even read the dictionary. Remember—you're a writer, not a reader.

- Talk to everyone about the trash corrupting the literary market these days. Not only will this make you sound like a knowledgeable writer, but you'll save hundreds of people from reading junk while they're waiting for your masterpiece to be released.

- Sit in coffee shops with your laptop. This is the essence of being a writer. Enjoy your coffee and pretend to be hard at work—one day people will marvel at the fact that they sat in the same room as you as you worked on the writing that changed their lives.

- Write only at the peak of your inspiration. If the muse isn't in it, you'll only write junk, which is a waste of everyone's time. Instead, enjoy the coffee smell and wait for the muse to impart the glittering, golden words that will make your writing so beautiful that readers will cry when they read it (but not you, because you're not a reader).

- Use big, flowery words. Simple writing is for the weak-minded. You can't change the world with your writing with plain Jane words. This is why Shakespeare made up so many new words while penning his masterpieces.

- Tweet about your writing every five minutes. This will not only prove to your followers that you actually write, but it'll make you instantly popular with other writers once you start telling them how game-changing your work is. Also, don't forget to use big words.

- Don't show anyone your work before it's published. Don't even show your mother—the temptation to plagiarize such beautiful writing will be too great. And who can blame them? You're the greatest writer to be born in centuries.

- Create a catch phrase. You're going to be a famous writer one day, so people will be quoting you all the time. Now is a great time to create a catch phrase, something that people will remember you by, something like, "I write beautifully, because the golden essence of the writer is within me" or something mature and thoughtful like, "Don't hate me because I'm beautiful, hate me because I write better than you."

Now go forth and write, my budding, master novelists! I'll be waiting for your brilliant writing to hit the shelves.

*= Why yes, this is a sarcastic post! Please don't take any of this seriously—and for the love of all things literary, do not do these things (except maybe make a catch phrase. You know. If you want).!

Now it's your turn: what so-called "tips" would you add to the list?