|

| Photo credit: @optikalblitz on Flickr |

First and foremost, the "aspiring writer"

does not exist—there is the writer and the not-writer, but you cannot aspire to

be a writer any more than you can aspire to be a reader (do you read or not?)

or an artist (do you create art? Yes? Then you’re an artist). If you want to be

a writer, the first thing you must do is eliminate "aspiring" from

your vocabulary. You either write or you don't. Decide.

But first make absolutely sure that you want

to be a writer—there can't be any doubts in your mind, you must know that you

want to write like you know that you need to breathe to live. The words

"maybe" "might" "perhaps" and

"possibly" are not acceptable terms. You must know this with your

heart, mind and soul.

Once you have decided that you are, indeed, a

writer, you must, of course, begin to write. Chances are if you're reading

this, you've already done so, but if you haven't you must begin immediately.

Write as much as you can—write awful, melodramatic poetry and ridiculous, clichéd

short stories and novels that go on for 100,000 words with little character development,

a bald, moustache-twirling villain and an ending that features your protagonist waking up and realizing it was all just a very strange dream. Share it

with your family who will tell you it's fantastic. Forget about editing and

write query letters to top agents around the country, then receive your first

and second and third and fourth form rejection letter.

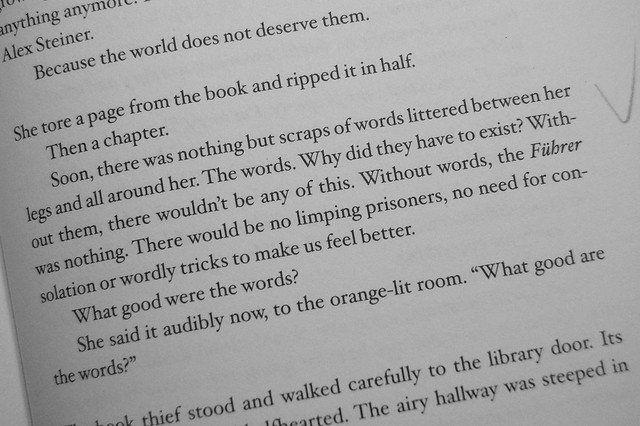

Throughout this time, you should be reading.

Read everything—trashy novels and books from the children's section and long,

classic novels that make you want to tear your eyes out. Read the good, the

bad, the ugly, the beautiful, non-fiction and novels, poetry and plays. If you

don't have time to read, then you most certainly don't have time to learn how

to write. Accept this and start reading widely, even if it means reading just a

couple minutes at a time.

Eventually, you will probably realize that

your first novel is terrible. This is good—it means you're learning. Don't let

it discourage you—put your first novel away and start the second. And third.

If you want to get serious about writing, you

must learn to edit. You'll have to make painful decisions—decision like tossing

the first 50,000 words of your first draft or eliminating characters entirely

or adding another 40,000 words to your novel long after you thought you'd be

finished.

Read about writing as much as you can—blog

posts, non-fiction, advice from agents and published writers—this is your bread

and butter, the food that will mold you into the writer you want to become.

Read it, apply it to your work then write some more.

Repeat.

Don't read about those writers who published

their very first novel and became New York Times bestsellers. Don't let

jealousy paralyze you when you see others around you get book deals, or when

your best friends become successful and pat you on the back as you continue to

slog through this disease called writing.

Accept that your friends and family will not

understand your passion. Don't let this stop you.

Over time you will get tired. You'll be

working a non-writing job or going to school or raising a family or all of the

above and there will be bills to pay and long hours at work and family members

who will smile politely when you talk about your writing and ask when you're

going to get published.

Know that it will likely be many years before

you see any of your writing in print.

Know that your debut novel will probably not

be your first book. Or your second. Or your third.

Know that even when you do get published,

chances are you'll probably still need that other job.

Know that there are much easier ways to make a

living.

Are you sure you want to be a writer? Are you absolutely

sure? Because the road of the writer is not an easy one—it's long and often

lonely and frustrating. It's exhausting and not unlike repeatedly smashing your

head into a wall.

Above all else: you must love to write.

If you're sure—if you know you love writing—then

know this: as long as you don't give up, you will one day succeed. It might

take two years or six or ten or twenty. It might be your fourth novel that gets

published or your sixth or your thirteenth. But if you're sure this is the road

you want to take and you devote your spare time to improving your craft and

falling in love with your stories over and over again, one day you'll make it.

Being a writer isn't always easy or fulfilling

or fun. But if you're sure that's who you are, don't let go of your dream—never

let it escape you.

Because it's up to you to make your dream come

true.

So now, tell me: are you a writer or aren't

you?