|

| Photo credit: CharliePev on Flickr |

Naturally in the discussion, the words referred to were curse words, but I think it's an important point nonetheless that goes beyond cursing in literature, because any word or phrase repeated too often starts to become a cliché.

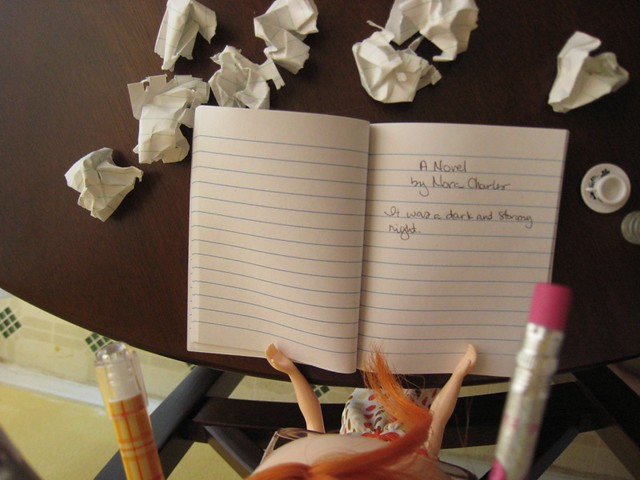

Most writers will at some point or another realize that they have a sort of crutch phrase, description or word. Sometimes it varies WIP to WIP, other times it's the same word or phrase that slips it's way into every manuscript you write. Whatever the case, it's not an uncommon plight for the writer.

And when you think about it, that kind of issue doesn't sound so bad. Sure, maybe you repeat a word or phrase a little more than probably necessary, but is that really such a sin in writing?

In short? Yes.

The problem with creating these sorts of clichés is that they don't go unnoticed. You see, writing is a tricky thing because your goal as a writer is to create complete images, worlds, characters, and scenes without bringing attention to the words actually stringing the story together. You goal as a writer isn't to rub oh, look at my gorgeous writing in the reader's face—it's quite the opposite, in fact. You want to tell a story with invisible words.

So when you create a cliché in your writing with a particular word or phrase, you're bringing attention back to the words themselves. The overused phrase becomes distracting, because even if only for a second, the reader will come across the words and think, hmm, I've seen that a lot. For a second, the reader has left the story and noticed the writing.

This isn't something you necessarily need to worry about while first drafting—in first draft mode you should be solely focused on getting the words down, regardless of how many times you've repeated a particular phrase. When you're editing, however, keep a sharp eye for potential overused words and phrases and cut them out before your readers notice your words.

It's not a particularly difficult fix (the find function of most word processors is a beautiful thing), but it's definitely one worth doing.

Have you ever overused a word or phrase? How did you amend the issue? Share your experience!